GOOD VIBES ONLY IS IMPOSSIBLE WHEN YOUR MOM IS DEAD

On Tolerating Discomfort

It’s been almost six months since my mother died and somehow I am still here. I keep waiting for the other shoe to drop. For me to be unable to get out bed or begin tempting fate with reckless, suicidal behavior. Instead, I find myself taking better care of myself than ever before. I have (finally) cut out weed. And I even reduced my sugar intake on the suggestion of my fertility acupuncturist. When I felt myself slipping into depression a few weeks ago, I responsibly went up on my mediation rather than letting go and falling into the open, appealing arms of despair. But instead of feeling proud of my resilience, I feel confused. My life now is objectively worse than my life before and yet…I am tolerating the very thing I always assumed would break me. Am I just avoiding my grief? Or is something else at play here?

As someone with near life-long OCD, discomfort is not unfamiliar to me. I spend my days afraid to touch doors, chairs and any kind of communal space. I worry about potential opportunities for contamination and plan my showers around certain exposures. I often feel jealous of anyone who’s mind isn’t filled with germ-based thoughts. Much like someone would daydream about being rich or famous, I daydream about being to go in an Uber without thinking about it or sit on a friend’s couch without disgust. That kind of brain seems too good to be true even though I know most people are walking around living my dream. (Or at least one portion of it. I would also love to be really rich and rather famous.) I say all this because I have little experience being completely at ease in the world, and I wonder if that constant hum of discomfort helped prepare me for this enormous loss.

I recently saw a TikTok from therapist RaQuel Hopkins that clicked a lot of this into place for me. She made the bold claim that the mental health industry has focused too much on pushing the idea of protecting your peace when really the better avenue for mental stability is increasing your tolerance for discomfort. When you live a life in search of constant peace, you have no choice but retreat from the world because you end up avoiding everything that makes you uncomfortable. You cut people out of your life. You avoid social situations. You resist taking big swings in your career to mitigate the risk of failure. Your nervous system might feel more regulated, but your world is rapidly shrinking.

As I often tell my coaching clients, avoidance make sense. Our anxiety and survival instinct want to protect us from anything deemed threatening. The problem is that our brains don’t do a great job of categorizing what is actually a threat and what is hard yet tolerable. And some of the rhetoric circulating online suggests that if the action you don’t want to do makes you feel bad, then you shouldn’t have to do it. I’m not going to argue that that isn’t true. Everyone gets to decide what they have the capacity for—especially in the hellscape that is 2025. But I think we often fail to ask the important follow up question: what am I sacrificing by not doing this hard thing? Sometimes the answer is not much. You can probably skip that uncomfortable conversation with your racist neighbor without real repercussions. But often the answer is that you are sacrificing a greater level of intimacy with your partner, stronger ties to your community and/or the kind of experiences that make putting up with distress worth it. (Here’s where I add the caveat that I am exclusively talking about things that don’t put you in danger—mentally or physically—or push you beyond what you can reasonably handle given your specific context.)

I think what often gets missed in online mental health discourse is that your goal shouldn’t be to achieve some level of enlightenment where nothing ever bothers you (impossible) or create a life where you never interact with anything bothersome (boring and small). Instead, we want to strengthen our tolerance for discomfort. Because once we know we can tolerate discomfort, it becomes easier to navigate a world that is filled with horrible things. We can switch our mindset from protecting our peace in this moment to forging through the distress to get to what’s on the other side. And the better we get at doing that, the more evidence we have that we can survive things we don’t like to do. Like continuing to live in a world without my mom.

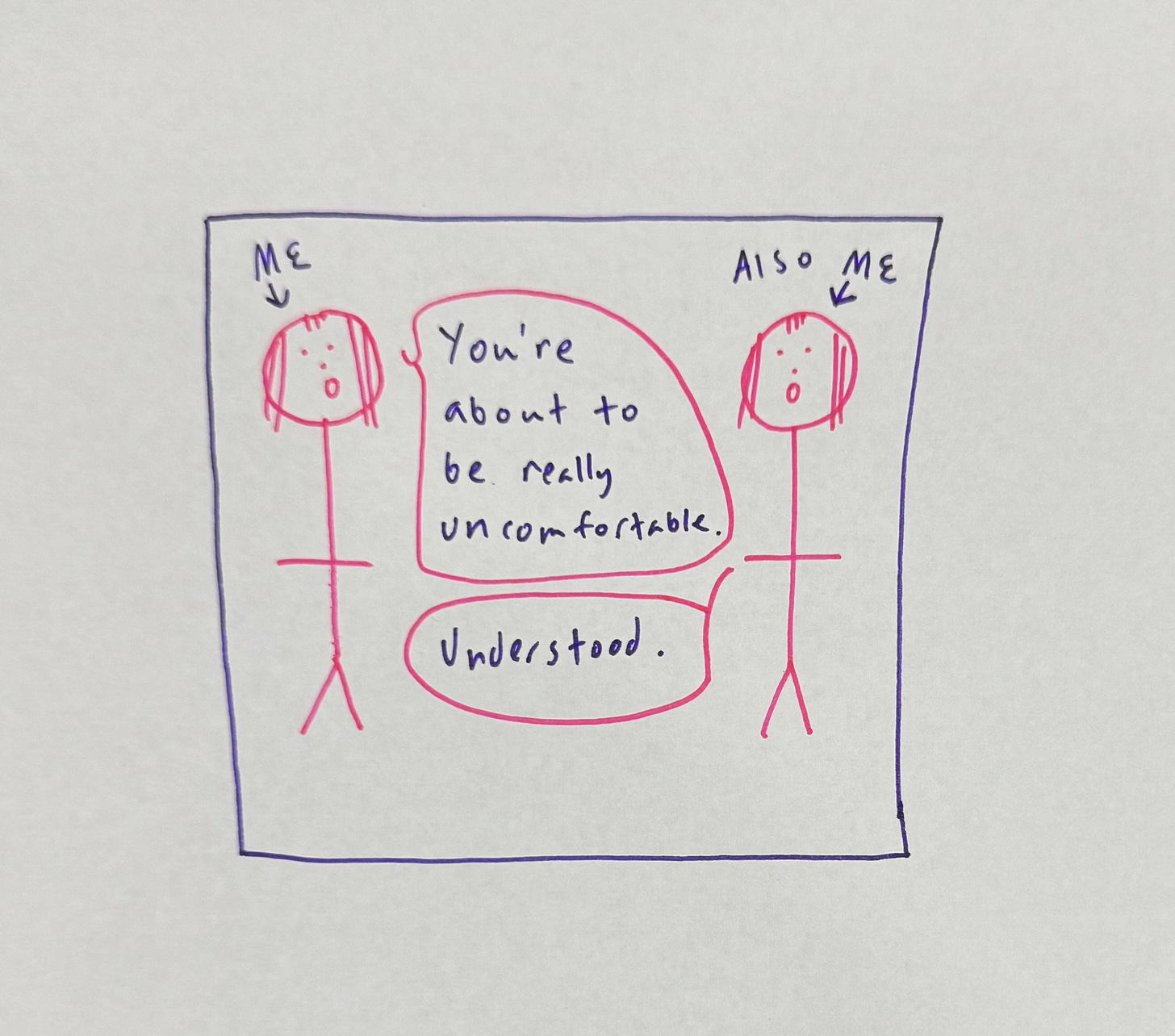

Accepting that certain things will simply be awful has been transformative for me. It is far easier to go into a situation thinking, “this is going to suck” than to try to mental gymnastics my way into feeling something other than dread. I now know for certain that I can handle, 1) having a bad time, 2) initiating difficult conversations and 3) seeing my friends with their still-alive moms. (Sitting on a public bench, not so much, but contamination OCD is beast of disorder, and I am chipping away at it at my own pace.) I am intentionally not trying to build my life around good vibes only. I am trying to build my life despite all the bad ones.

Grief is a form of discomfort that never goes away. It is the ultimate exposure therapy. But if I can stay engaged in my life despite that gnawing pain, I can probably do a lot of other things I didn’t think I could do before.

xoxo,

Allison

P.S. It would mean a lot to me if you hit the like button to increase chances of engagement! Also, if you are able to upgrade to paid subscriber or share my posts with a potential reader, I would be incredibly thankful! Thank you for reading!

P.P.S. If you are interested in working with me as a relationship coach please check out my website for more information.

I regularly read parts of your newsletter out loud to my therapist and she told me to thank you for helping me articulate a lot of the things I’ve been feeling. She also says “yeah I told you that too you know”

Thank you for your work. I lost my mother in November and I've been trying to navigate everything without her. Your journey through grief has helped me so much with connecting with my own grief